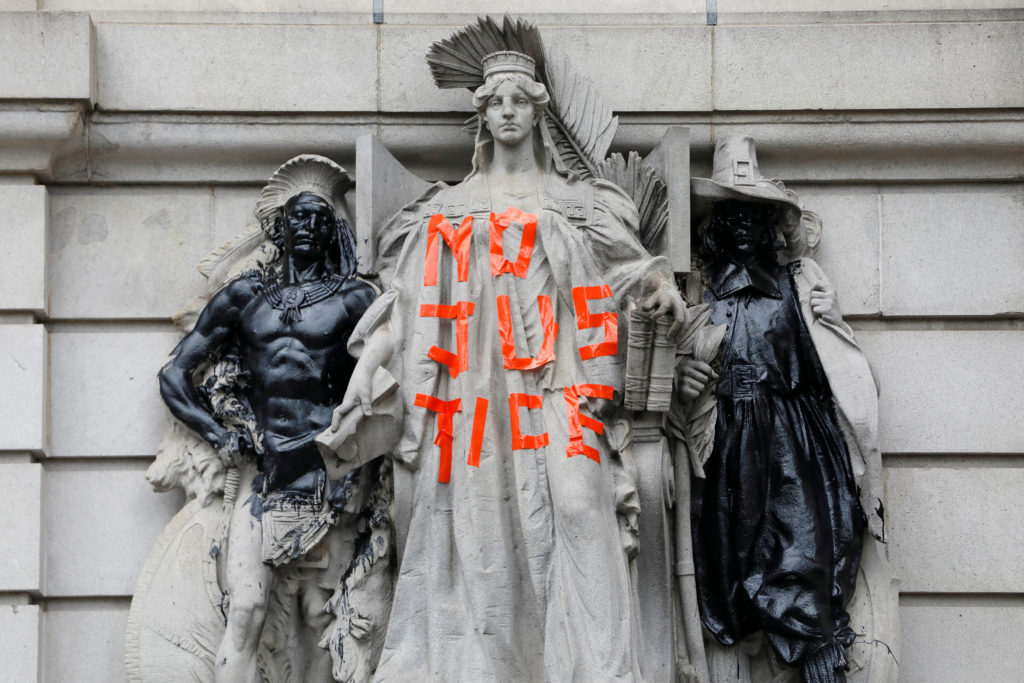

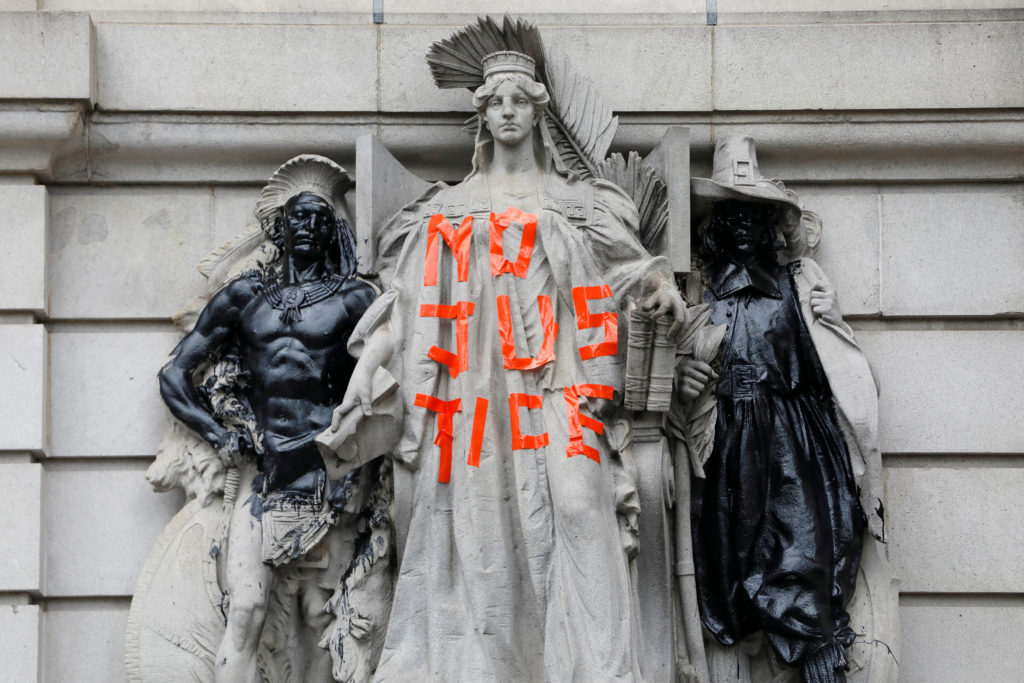

The murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer spurred what historians call the largest protest movement in U.S. history. Over the course of the next year, a reckoning over racial justice prompted concrete changes in policies and politics, and it changed the conversation surrounding racial justice forever. But Black Lives Matter, like major civil rights and social justice movements before it, has also generated backlash, as police clashed with protesters and threatened press freedom, and in the halls of power, where lawmakers have proposed a wave of anti-protest measures, alarming civil liberties advocates.

To understand how the First Amendment powers social justice movements like Black Lives Matter — and protects the right to protest, speak out, film police doing their jobs and more — FAC spoke to Constitutional law scholar Margaret M. Russell, who teaches at Santa Clara University School of Law. This interview is part of a series of interviews on the power and peril of speaking out, standing up for and documenting the movement for Black lives.

This interview was conducted in July 2021 by FAC intern Cricket X. Bidleman and has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: The recent movement for racial justice is historic by many measures. An analysis by the New York Times suggests that it may have been the largest protest movement in U.S. history. The demands made in the streets and in halls of power have led to changes in both public policy and public opinion. But we have also seen backlash. PEN America documented an explosion of anti-protest measures introduced in dozens of statehouses. Does any of the backlash surprise you, given historically what happens in response to big social justice movements?

A: It is not new, but there is great cause for concern. Perhaps more than ever.

The U.S. Supreme Court, under the Warren Court, had really defined First Amendment freedoms in a much more uniform way. The more you have state and local carve-outs, the more chance there is for a kind of anarchic, state-by-state hyper-prosecution of free speech. These [anti-protest bills being proposed today] include expanded, broad definitions for conduct that is deemed to be riotous, trespassing, obstruction of traffic, etc. The problem, under the First Amendment, is really that when you define crimes broadly and vaguely, that creates what’s called a chilling effect. People don’t really know what is being criminalized, so it tends to really tamp down on protest.

Even though these [types of anti-protest measures] are not new, they are expanded and they are, as I said, hyper-prosecutorial, and they are great cause for concern.

Recommended reading:

Q: Is the federal civil disorders law that Congress passed during the Civil Rights-era and anti-war movement an example of government backlash to demonstrators?

The original Civil Obedience Act was passed during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, and it’s well known that the intent was to tamp down on protest. It has not been used often between the Nixon administration and now. Just in the past year, it was used to bring in the federal government, under the Trump administration, to go in and file prosecutions in areas in which typically state and local authorities would be in control. The way this operates as backlash is, take a city like Portland, Oregon, that had a lot of Black Lives Matter protests. And local authorities were deciding on their own how to handle those prosecutions, how to handle those arrests, generally in a much more speech and First Amendment-respecting way. However, under the Trump administration, the Justice Department disregarded the local way of treating things and said we’re going to go in and file federal charges.

The statute itself refers very specifically to definitions of crimes that were already crimes, such as property damage and riot conspiracy, and it creates a new cause of action, a new statutory crime out of them. The way this actually tamps down on both civil disobedience and lawful assemblies is that it creates a new federal crime with a lengthier criminal sentence, with the possibility that a felony conviction on the federal level may prevent someone from getting a job or having access to the vote for a very long time. This was actually creating a civil obedience statute to criminalize in an era, meaning protests, in which there were already underlying possibilities for curtailing any unlawful conduct.

Recommended reading:

Q: Does this illustrate why we should be skeptical of state or federal laws that criminalize or otherwise curb speech and assembly rights? And does it speak to who has the power to march and to speak. There’s the concern that those challenging power structures and marginalized communities are often the ones being targeted.

A: In the history of First Amendment jurisprudence before the Supreme court, that has always been the case, that the people who are singled out and targeted for lawful exercise of their First Amendment rights are typically the marginalized. [In] the early cases of the First Amendment in the early 20th century, some of the original prosecutions under federal and state law were against lawful anti-war protestors — people who were not engaging in anything related in any way to violence, but who were standing up against World War I. Those prosecutions and that form of First Amendment law really started the path. Jump forward to the 1960s and ‘70s, in which a much more liberal U.S. Supreme Court than now — the Earl Warren Court — took cases coming from the Civil Rights movement involving the free speech and assembly rights of civil rights protesters. [The cases] clearly established an area of First Amendment law — that speech, assembly, and petition go right to the core of the Bill of Rights protections and have to be articulated and protected very firmly against governmental power. When you ask about the state, local and federal overreaching right now, they are really attempts to push back against very clear First Amendment precedent protecting expression.

He and others from the 1960s Civil Rights movement have become very involved in the Black Lives Matter movement — showing up, drawing the parallels and the analogies. By reinforcing this legacy for protection of freedom of speech — speech that is loud, speech that is disruptive, but speech that is peaceful — by doing that they have really created the link between the 1960s and now. They have helped remind Black Lives Matter protesters that they’re engaging in a patriotic act, even though the word “patriotism” probably isn’t one that many students today would use. It is ultimately patriotic, because it is for the good of the country, and for the furtherance of social justice.

Q: What do we know about the current Supreme Court’s views on First Amendment freedoms, specifically freedom of assembly?

A: What we know from recent history is that the court majority certainly has a pretty strong record in terms of protecting speech and assembly. They have taken cases that, I think, are very controversial in terms of their facts, but ultimately they have made a ruling in favor of giving strong emphasis to First Amendment rights. For example, a while back but still relevant to today’s court, it took up a case that has to do with a homophobic and, at times, hateful group, the Westboro Baptist Church, and protests they have in public areas, including funerals. The Supreme Court was very clear in that as hateful as that group’s speech is, it was not unlawful and is protected under the First Amendment. Fast-forwarding to a case from this past term [there is the] challenge of a high school student who used profanity in her own private social media that was reported to the school and used as a basis for punishing her. The Supreme court recognized that that was freedom of speech. I think that the emphasis in the current court is to rely on precedent, and to recognize that free speech, assembly and petition are important. (See Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.)

The reason why I keep harkening back to the Warren Court is because the Warren Court is really historically thought of as bold and very forthright in articulating the importance of individual rights like freedom of speech. They did so during an era in which the cases that they took involved the rights of racial minorities and advocates for social justice. The Supreme Court today is relying upon those cases, which I don’t think is a particularly brave act. I somehow doubt that they would have granted review in the same kinds of cases of protesters in the ‘60s that the Warren Court did. And I doubt that they would necessarily have reached the same result, with the kinds of important rhetorical emphasis on freedom of speech for the marginalized. I don’t see that coming from today’s court. They don’t accept that kind of case, generally.

Q: Do you have any thoughts about generational perspectives on First Amendment principles? There seems, at times, a tension between some free expression principles and the social justice movement.

A: I’ve taught many students over the years who, before they take constitutional law, don’t have an analytical or intellectual framework for looking at questions like the difference between hate speech and hate violence. That’s not an easy thing to understand. You can have constitutional hate-crime regulations, but you can’t have constitutional hate-speech prohibitions unless there is a clear and present danger or something. That’s a pretty hard thing for people new to the First Amendment to understand. What I’ve learned from students is that when I have taught hate speech over the years, and I start off by explaining “hate speech, per se, is protected under the First Amendment and here’s why and here’s how it’s defined,” I have heard much more from the historically-suppressed voices, and I respect them. I don’t call it cancel culture. I don’t call it snowflakes. I don’t call it politically correct. I am hearing the genuine voices of people who see the link between hateful speech and their, let’s say, gender identity or their racial identity. In having that engaged discussion, I think we both come away with (the professor) with a deeper understanding of the genuine harm caused by hate speech even though I know it is constitutional, and the students come away with an analytical framework for understanding why you always have to be vigilant when you’re restricting any kind of speech, when the government is given that kind of power.

Recommended reading:

Q: Is anything else that you think we should know?

A: Especially because the subject is freedom of expression and the importance of that right in the context of protest movements, I’d like to say that the protests of the last year since George Floyd’s murder have really changed our lives in some pretty significant ways. I hope that they continue, and I hope people don’t, sort of, fall back asleep.

About Margaret M. Russell:

Margaret M. Russell teaches at Santa Clara University School of Law. She is a frequent media commentator, op-ed contributor and speaker locally and nationally on issues related to law and the Constitution. Russell has been a visiting scholar at Columbia University and a visiting professor at Northeastern University. In 2014, she was awarded a Fulbright research scholarship to work with women judges in Tanzania. Her research focus is U.S. civil rights and civil liberties. Her publications include The First Amendment: Freedom of Assembly and Petition (Prometheus Books). She is a co-founder of two nonprofits, the East Palo Alto Community Law Project and the Equal Justice Society, and an elected member of the American Law Institute. Her past board service includes the National American Civil Liberties Union and the American Constitution Society.

About Cricket X. Bidleman:

Cricket X. Bidleman is the First Amendment Coalition’s summer 2021 intern via Stanford University’s Rebele Journalism Internship Program, which gives Stanford students the opportunity to gain journalistic work experience by providing stipends for internships with qualifying organizations.

Additional credits:

This project is directed by Ginny LaRoe of the First Amendment Coalition and produced by Dana Amihere of Code Black Media. To contact the First Amendment Coalition, write to FAC@firstamendmentcoalition.org.